City of The Hague

Jerryt Krombeen works at the planning department of The Hague, The Netherlands. The city is at the heart of the political functions. As many Dutch cities, main challenges include an increasing housing demand (100.000 more inhabitants till 2040) combined with the necessity to provide a diversified job market. This tension is leading to a harsh competition for space to build houses and workplaces combined with an acceleration of the gentrification processes. Given this context, Jerryt presented the implementation program for the Binckhorst area, a former industrial neighborhood well in the center of the city, very accessible and connected to the transport infrastructure where very expensive real estate redevelopment could have happened but have been put aside to diversify the allocation of spaces for business and production, hence maintain available space for the economic activities.

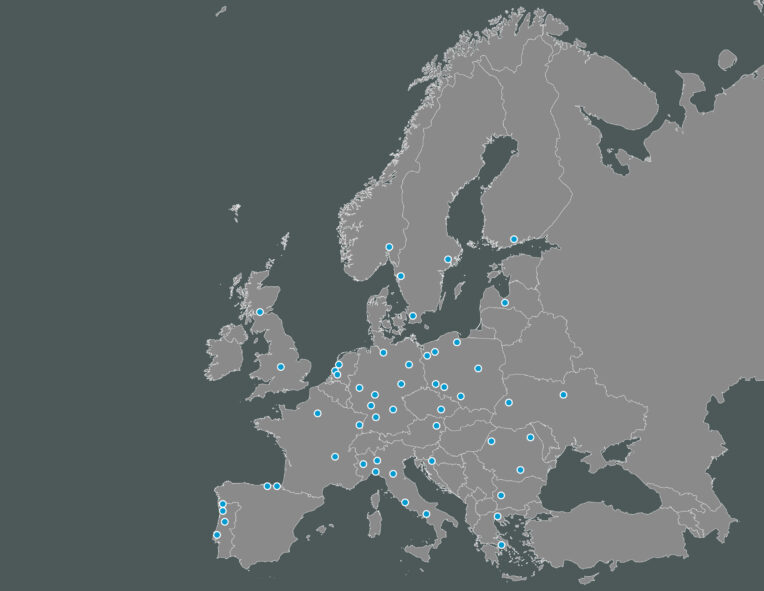

There is an increasing awareness of the public authorities across Europe that housing production is threatening the presence of other functions within the city while subtracting valuable land to create workplaces (industrial sectors, businesses and companies) forcing the Municipality to elaborate on a different spatial business model to oppose these trends.

What is a stake?

Like a well-functioning ecosystem, there is the variety of companies and jobs that can afford a space within the city boundaries.

The victims of the gentrification are leaving the city: first in the list, the companies which require large amount of space such as the manufacturing sector, move away. The decline in The Hague is already visible.

An experimental model

The experimental sector of the Binckhorst is the Mercuriuskwartier. A fresh mind-set change was necessary to propose a new spatial business model which includes pivotal concepts:

- value the traditional industrial zones maintaining the quality of the place and trying to densify them (Groothandelgebouw in Rotterdam built in 1953 and home to 450 companies was brought as an example (https://ghg.nl/about/) together with the Lingotto the automobile industry Fiat major artifact. Buildings like these will maintain their value and offer company spaces over a longer period than cheaper built versions (making them venerable to be taken over by more profitable functions). (https://www.dezeen.com/2021/10/22/benedetto-camerana-lingotto-building-fiat-turin/);

- rethink the connections with/through the rest of the city: in terms of the logistic meaning of industrial zones (goods coming in by bulk and are sold in products or pieces) and, in this case, also a tram line has being planned;

- secure the public support to the companies which invest in the area by defining a clear strategic vision and plan of action. In this case, it was done by highlighting the elements necessary to the operation:

> Economic profile of specific target group: commercial functions (trade companies and manufacturing light industries), delivery and large scale retail;

> Building program with guidelines: value large scale plot sizes which define the unicity of the district in the city (the only area in the city where such big lots are available and companies of this scale still function);> Public space framework (based on the quality of the area): the spatial framework is organized around the concept of climate-friendly and worker/user-friendly public space to improve accessibility for companies, facilitating different scales of transportation;> Operational strategy and business model: the novelty is the use of the municipal properties for the development of companies even if this strategy is not financially feasible stressing on the experimental dimension of this model.

The Public policy and strategy will support the area’s development trying to match the need of vacant places.

Conclusive reflections

The spatial implications are clearly visible: the northern sectors of the district are characterized by the extreme large plots up to 12,000 sqm, while the historical industrial heritage located in the central areas will be mainly developed by the City through stacking mix of uses and functions (including small businesses but also sport activities and cafés).

The City is aware that when deciding to exclude housing, the question of how to keep alive the neighbourhood after the activity close down is very relevant. Also, the business case will miss a profitable part of program that could compensate for the large investments. If the ambition is to create an attractive and livable plan, addressing the impact of the noisy and dirty companies become a must. That is why the process of stacking becomes a major strategy for the entire plan to work with. Though complicated to implement and to make it function, this is the only way the city can keep up with the hunger for business spaces while making the economic environment healthy and future proof at the detriment of a vital and positive economy.

The final remarks was related to the coexistence of productive activities and housing developments where already being planned. The answer in the Mercuriuskwarier is that the housing projects are forced to make 20 square metres of business space per housing unit, so they need to compensate for all the business spaces they are taking away from the market. In this way, also the housing projects contribute to almost 7000 square meters of business space!

Such models also require new forms of facilitation enabling to soften and mediate on friction or tensions between differ kinds of activities/stakeholders. In many ways, regardless of the legislation and what the rules are, this is all very much about the social dimension of the city, it is about people and relationships.

Back to the Productive Cities Expert Group Meeting – November 2023